Mort Gets a Thank-you

It was an overcast Tuesday in May. Low clouds hung over the valley’s hills like a gray shroud threatening much-needed rain but yet to deliver. Winter had brought early hope and then reneged on breaking the three-year drought; the townsfolk now worshiped every rare drop that fell like unkept promises. The threat of a devastating fire was the topic of every regular coffee shop conversation, and there were an abundance of coffee shops in the small town nestled in the valley between two mountain ranges.

As he did every morning, Mort walked along Main Street on his way to his morning bagel and coffee at The Nosh and Kvetch Bagel Shop, known by regulars as N & K’s. Medium height, slightly bent at the waist, he walked with a purpose honed after an almost forty-year career as a middle school English teacher. His retirement came just before cynicism set in and the bureaucracy became too much to bear. He was a relatively happy man with a noticeable paunch, glistening blue eyes, and always wearing a fisherman’s cap covering thinning hair. If it was cold, he wore a Navy-blue pea coat; cool, a light jacket; warm or hot, a loud Hawaiian shirt.

He was always the first customer at N & K’s and sat in the same booth in the far corner, the only one without a window, waiting for his longtime friend Al to arrive. Portia, a tall, elegant former ballet dancer, and owner of N & K’s immediately came over and poured Mort a mug of first-of-the-morning coffee and told him his bialy with a schmear would be ready in a minute. She was one of the few African Americans in town and seemed to know as much, if not more, Yiddish as the Jews who frequented her shop. Mort and his friends found it a quaint anomaly and Portia laid claim to her knowledge as a result of growing up in South Philly.

After taking a sip of coffee and proclaiming it hot enough, Mort pulled a stack of plain, white notecards from his coat pocket and a well-used Pilot fountain pen from his shirt pocket and began writing his daily five thank-you notes to a variety of known and unknown people. He wrote notes to folks he read about in the newspaper or from stories he heard on the television news. To the boy who won the elementary school spelling bee; to the woman who knitted caps for soldiers; to the dog walker featured on the evening news who gave complimentary walks for those unable to exercise their furry friends; to any local who did something kind. He had always been a penner of notes. He made a habit to write notes to his students and their parents praising even the most minor of accomplishments. However, the notes he wrote while drinking coffee and munching on his bialy with a schmear were never sent. Instead, they were filed in three-by-five, plastic boxes, labeled by the year the notes were written, and neatly stored on his home office bookshelf next to a collection of obsolete teacher’s editions of language arts textbooks.

Al strode in, waved at Portia, and sat across from Mort. If Mort was old school, fountain pen and note cards, Al was everything he thought modern: wearing a hipster hat, Nat Nast shirt, stylish jeans, whatever shoes teenagers flaunted and carrying the latest and most powerful smart phone currently available. None of it made any sense to Mort, who thought his friend of almost forty years was a bit daft for donning clothes that looked silly on a balding, six foot five, ectomorph with very little muscle tone who walked with a slouch and had no idea how to take full advantage of the electronic power he held in his left hand. Mort thought of Al as a billboard for how not to grow old with dignity. Yet, Al was the one friend to whom he could confide his deepest secrets ever since they met as first-year teachers.

Portia set a steaming cup of chai before Al, glanced at his new fedora, and suggested the lox and onion omelet.

“That would be perfecto,” said Al. “And how’s your Brutus today?” referring to Portia’s husband Tom who did the cooking and never engaged with the customers.

“Oh, you know, conspiring as always,” replied Portia with a smile before turning and heading to a table where another group of regulars sat.

“I see you’ve got a nice stack of thank-you notes that will never be sent.”

“It’s the thought that counts,” replied Mort with his usual cliché. He lowered his voice and said, “Al, the strangest thing happened on my walk over this morning.”

Mort described how an unknown person ran up behind him and pushed a card into his coat pocket before running away. “All of a sudden I felt a hand in my pocket and this person dressed in all black and wearing a hoodie run off. I couldn’t tell if it was a man or a woman. I pulled this card out of my pocket.” Mort showed Al the card which read, “You changed my life.”

“Well, at least someone out there believes in delivering thank-you notes.”

“You’re assuming it’s a thank-you note.”

Portia set Al’s omelet down and refilled the coffee cups. Al took a bite and proclaimed it excellent. “Tell me again, Portia, how does a beautiful Black woman from South Philly who knows more about being Jewish than Mort or moi own a bagel shop?”

Portia replied as she did every time Al asked, “Ethiopia by way of Israel with a dose of Philly culture as my guide.”

And Al sang, as he always did when he and Portia engaged in banter, “We are the world, we are the children, we are the ones who make a brighter day.”

“So true, Al.”

“And yet it all comes down to bagels,” laughed Al.

“And the kvetch.”

Al examined the card, which was mysteriously put into Mort’s pocket, and suggested it was from a woman. Mort asked how he could tell and Al said the block printed letters had a certain flourish making the writing more of a feminine hand. “Besides, I don’t think men write in orange ink. I think what you have is a secret admirer.” Al returned the card to Mort and paid closer attention to his omelet.

“I doubt that. Besides Effie is the only admirer I need.” Effie was Mort’s wife of over thirty-five years. She was a Rubenesque woman of sturdy stature, bawdy laugh, and a stove that produced meals fit for a dozen even when it was just she and Mort for dinner. Their four grown children, two sons and two daughters, made a habit of dropping by unannounced during mealtime knowing there would be plenty for themselves and the grandchildren. Their kids had a way of communicating with each other so that only one family ‘came by out of the blue’ at a time. Two or three times a week, the front door of their home would open just before the 5:30 dinnertime, and Effie would exclaim, “What a nice surprise! I’ll set the table for guests.” Then she would wrap her fleshy arms around each son or daughter and the grandchildren, pull them down to her level and kiss each of them on the forehead, before moving the two place settings from the kitchen table to the dining room table and arranging additional settings. Mort always shook his head knowingly and directed his son or daughter to open a bottle of the good wine and then inform him of how they happened to drop by. The stories were always creative and Mort relished the fiction.

Al remarked, “One can never have too many admirers. It’s like having a blood bank for the soul.”

“I think you mean friends,” said Mort.

“Perhaps.”

Before leaving, Mort and Al made it a point to wave at Portia and point to the cash they had left on the table, which always included a generous tip and a thank-you note from Mort. Unlike the notes he would file when he got home, it was the only note Mort delivered and he always wrote, “Thank you for giving my day such a good start. You’re the best!” What Mort didn’t know was that Portia would deposit each note in a plastic garbage bag labeled “Mort’s Notes” which hung in the utility closet in the rear of the kitchen. When asked by the custodians who cleaned after hours why she kept them, she easily replied, “He’s a rare bird and I’m not about to discard a nice gesture.”

The next morning, Mort was extra alert and cautious as made his regular walk. He looked from side-to-side, pausing a few times before entering the N & K. Portia held a pot of coffee in his direction and nodded towards his table. As he began to scoot into his booth, he noticed a card on the seat. He picked it up, turned it over, and read, “Seriously, you changed my life.”

Portia came over with a heavy ceramic mug and poured him coffee. “Another note, Mort?”

“It was on the seat. Did you see who put it there?”

“As always, you’re the first one in,” said Portia. “I have no idea how it got there. I’ll get your bialy ready.”

Mort examined the card. It was printed in the same orange block letters as the first one, clearly by the same hand. The card was identical to the ones Mort used. He wondered who might have written the notes. A former student? Someone with a grudge? Someone simply playing mind games? Mort never saw himself as a popular teacher among his students, or one who received elevated respect from colleagues. For holidays, other teachers often received thoughtful and sometimes extravagant gifts. Al was an idolized math teacher and carried boxes of gifts to his car before winter and spring breaks and even more boxes before summer vacation. Mort was given few and usually just a holiday card from a smattering of students. Mort thought of himself as a journeyman who skillfully taught his students the required curriculum without any special flourish. While known for his frequent thank-you notes, most of his students viewed him as old-fashioned and out of touch with popular topics and current events.

“This was here when I arrived,” said Mort showing the card to Al who arrived earlier than usual and before Mort had a chance to begin writing new thank-you notes. “I think I’m being stalked. Who would want to harass me?”

Al took the card and remarked sardonically, “Having a stalker might be the greatest compliment you’ve ever received.”

Portia approached with Mort’s bialy, a coffee pot, and a mug for Al. “I think I’ll change things up this morning, Portia. How about black tea and a ham and cheese omelet?”

“You know we don’t have ham, Al.”

“All of a sudden you’re kosher?” questioned Al. “Has the world flip-flopped?”

“No, we just don’t have ham. We do have Canadian bacon and regular bacon. No ham.” Portia stood before Al with her perfect posture, unblemished café au lait skin, and a close-lipped smile that projected mirth and patience.

“What difference does it make?”

“It’s what sells, Al. We don’t sell ham. No demand. We don’t have pork chops either,” Portia remarked now with a toothy smile and a wink toward Mort, who understood her jest.”

“I think Ethiopia created a lost tribe that’s still trying to find its way,” said Al. “Okay, I’ll go with a Canadian bacon and Swiss cheese omelet with a toasted plain bagel. Oh, and regular hash browns, not that souped up version with all the onions and peppers.”

Portia quickly returned with Al’s tea and mentioned, “The cook salutes you, Al.”

Al handed the card back to Mort who had been enjoying, as he always did, the banter between Al and Portia. He also knew that ham was available, because, unlike Al, from time to time he read the menu. He knew that Portia playfully refused it to Al and that Al enjoyed Portia’s denials.

Al suggested that Mort’s secret stalker was probably Portia. Al said that he would have known if it was Portia when the runner placed the card in his pocket. “Besides, Portia was already here when I arrived. No, it must be someone with a grudge. Perhaps, a former student who earned a poor grade.”

“People with grudges don’t write ‘you changed my life’ notes.

“I don’t think I was ever a life changer.”

Al asked Mort if he knew about the butterfly effect. He explained how the flapping of a butterfly’s wings in Asia could impact the weather in North America. “Tiny actions can create massive results. Your small teacher acts may have caused a tsunamic effect for someone else.”

“I doubt I ever caused more than a ripple, much less a high tide.”

Portia returned with Al’s omelet. “Here’s your ham and cheese omelet with your boring bagel and even more boring potatoes. The cook made a special run to Safeway for your ham.”

“Many thanks for the service. I’ll be sure to return tomorrow,” laughed Al. “Big tip today!” he added with a flourish.

Later that day, Al told Effie about the first and second notes. Effie listened before informing Mort what she found on the windshield of their fifteen-year-old Prius, which had been driven less than 50,000 miles. Effie and Mort rarely took vacations by car; they hardly vacationed at all. Their children had given them an anniversary gift of two weeks in New York City with arrangements for them to see a play or musical production every day they were there. There was the one trip to Israel with a group from their synagogue shortly after Mort’s retirement. Portia had been an invaluable source of travel information, which they used well on those few open days on their tour’s itinerary. For example, where to taste the best shawarma, tastiest falafel, and how to bargain for jewelry at the markets in Old Jerusalem. Although Portia had grown up in Pennsylvania, she and her family often visited relatives in Israel and, after graduating from high school and enrolling at Penn on a full scholarship, she spent a gap year living with an aunt and cousins in Tel Aviv.

Effie continued to listen as Mort described how the cards were delivered, one surreptitiously by an anonymous runner and the other left on his booth’s seat for him to find. They sat opposite one another in matching wingback chairs that had become saggy and slightly threadbare. Mort sat low with his legs crossed. When Effie sat, she appeared as tall as she was wide, like a cuddly stuffed bear wedged into the chair.

“Al thinks it’s a female’s handwriting, but it’s hard to tell.” He showed the cards to Effie who agreed that block printing made it difficult to identify gender. “It’s so strange, Effie. What do you think?”

Effie considered the two cards: ‘You changed my life’ and ‘Seriously, you changed my life.’ “I wonder why there is increased emphasis in the second card. Everyone takes you seriously. I think that’s why Al is such a good friend. Nobody takes him seriously,” gushed Effie with a laugh so loud and only tolerated by her family and friends. “I wouldn’t make much of it. It’s nice to know that someone out there is so appreciative of you. And, by the way, there was a third card. I found in on the car’s windshield this morning.” Effie pulled the card from her apron’s pocket and handed it to Mort. It read in bright orange ink, ‘So thankful you changed my life.’

“This was on the windshield while the car was parked in the garage?” asked Mort with a measure of disbelief.

“Yes, I found it this morning while getting some laundry detergent.”

“In the garage where the side door is always locked and I can’t remember the last time the garage door was open.”

Effie thought for a moment, her eyes closed and her fingers drumming her lap. “How could that be?”

Mort rose from his chair with a trace of a grunt and walked to the kitchen and through the door leading into the garage. He checked to see if the outside door was locked and found that it was and without any sign of it being forced open. He returned to the living room chair and sat with another trace of a grunt and told Effie that the garage was secure.

“You’re sure the garage door was not left open for a while when you were doing something else?”

“We haven’t driven the car in over a week, the last time we went grocery shopping. There’s been no reason to open the door.”

“This is very strange. I’m not sure what to make of this,” said Mort while tugging at his right ear, a habit he had developed when trying to think things through.

Effie pointed at Mort and with her usual loud, but loving tone said, “Someone simply admires and appreciates you. Now, I need to get dinner going. I have a feeling we’ll have company tonight.” She rose from her chair without a sound and headed into the kitchen. Mort remained sitting like a confused puppy needing direction from his trainer.

Mort slipped into his booth, waved at Portia who was tending to another early morning patron, and felt relief that there were no new notes to be discovered and surprised that he was not the first customer. He took out a short stack of notecards and his fountain pen and wrote his first thank-you of the day, “Thank you, whomever you are, for not mysteriously leaving me a card today. I hope you will reveal yourself soon.”

Portia set a hot mug of coffee before Mort, confirmed his usual order, and turned to find Al standing next to her smiling like someone with a secret that wouldn’t be shared.

“How’s the beautiful Ethiopian Jewess this morning?”

“You know, Al, your advancing years does not give you license to be so grossly inappropriate.”

“I apologize for being in awe of such a divine creature as yourself. And one of my culture, to boot.”

Portia paused with a pot of coffee in one hand and the other on her hip. “You know very little of my culture and I doubt much of your own, Al. Plain bagel and a lox scramble today?”

“Sounds good. And it may surprise you that I might know more than either you or Mort.”

Mort watched this exchange feeling a shiver of shame for his friendship with Al and a lot of respect for Portia’s ability to stand her ground without sarcasm or contrived attitude.

“Another card was left on my car’s windshield while it was parked in our locked garage,” said Mort with obvious distress in his voice. “Who and how did someone get in my garage? Effie found it. She doesn’t think it’s a big deal. She says I have a secret admirer.”

“One of your kids, maybe,” suggested Al. “Or perhaps a grandchild. Or maybe Portia, she seems to have taken a liking to you.” Al looked at the card that Mort had written to his anonymous writer. “Now, this one is truly undeliverable and not worth the energy you are putting into it.”

“I don’t know what else to do.”

“Just accept the fact that you had a positive impact on a former student and let it be.”

Several weeks passed without any more secret notes. Mort kept to the usual rhythm of his days, writing thank-you notes, meeting Al at N & K’s for his usual coffee and bialy with a schmear, Al’s feigning alarm at not being able to order a ham and cheese omelet and then being served one by the elegant Portia who always remarked with reserved sarcasm, “he ran over to Safeway to buy ham just for you, Al,” and the ambiguity he felt over Al’s inappropriate speech with Portia.

One day he was sipping his coffee and enjoying his bialy with a schmear. He began writing a thank-you note to a good Samaritan he had spotted picking up dog poop after an inconsiderate dog walker failed to do so when Portia slid into the side of the booth reserved for Al. Her face was serious like those frequent times one of his former students would approach with the news that he had lost his homework assignment and was hoping to be given an extension, which Mort always granted.

“Mort, I need to ask, how many years have you been coming here every morning, ordering the same thing, writing thank-you notes, kibbitzing with Al, and then leaving a generous tip and a thank-you note?”

“I think about three years.”

“Well, today’s note will make it an even 800. I know this because I’ve kept and counted all the cards, all the cards with exactly the same message. When you consider we are closed on Sundays and on major holidays and those few weeks I’ve taken for vacations, it’s been a little over three years. I appreciate the tips and the notes. By the way, I can put up with Al’s idiotic talk, which I take mostly as an alter kacker’s feeble attempt at charm, however misplaced. But why the undelivered notes. I’ve never asked, but after three years I want to know.”

Mort sat like a contrite poodle who knew he did something wrong but wasn’t sure what. He looked at Portia for a moment before wiping his lips with a napkin and clearing his throat.

“I’ve never been asked. My wife thinks it’s cute. Al believes I’m simply meshuga. I’m surprised that you’ve kept all the notes. So, I’ll tell you why.”

It felt unusually quiet inside the Nosh & Kvetch. All the other booths were empty and Al had yet to arrive. Portia’s face had changed from overly serious to more neutral anticipation.

“It’s all about gratitude,” said Mort.

“Gratitude.”

“Yes, gratitude. I once read about the benefits of keeping a gratitude journal. How the daily affirmation of gratitude could be life enriching. I’ve never been much for New Age philosophy, but I was struck by the notion of a personal exclamation of gratitude, or, in my case, thankfulness. When I was a teacher, I had always written thank-you notes to my students. I think they thought it was corny and I’m sure they ended up in the trash without a second thought. I’m sure I wrote those notes as a way of somehow controlling their behavior or at least trying to use praise to encourage repeated good deeds. I realize I expected something in return for saying thanks. Now I write notes to remind me of how much I have to be thankful for without expecting anything in return.”

“Then why am I the only one who gets a note?”

“I think it’s because you go out of your way to make me feel special every day. And, of course, you go out of your way to irritate Al with your ‘he ran over to Safeway to get your ham’ remark.

The N & K’s door opened and Al walked in and approached. Before sliding out of the booth to make room for Al, Portia leaned across the table and whispered, “You’ve changed my life, Mort.”

“You’re the secret note writer,” said Mort with relief.

“No. I’m not.”

….

This short story is from the book Unknown & Other Stories by Barry Vitcov (Finishing Line Press), and can be found at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/unknown-other-stories-by-barry-vitcov/

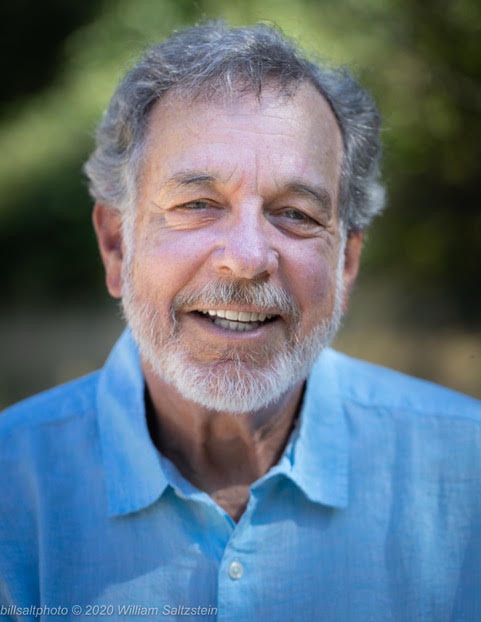

Barry Vitcov lives in Ashland, Oregon with his wife and exceptionally brilliant standard poodle. His poetry and short stories have appeared in a variety of publications, including: EAP: The Magazine, Literary Yard, The Scarlet Review, Fiction on the Web, Labyrinth, Mobius Blvd., Black Sheep, Dark Horses, Jefferson Review, and The Rapids: An Art & Literature Journal of Southern Oregon. He has had four books published by Finishing Line Press, a collection of poetry, Where I Live Some of the Time (2021); a collection of short stories, The Wilbur Stories & More (2022); a chapbook collection of poems Structures (2024); and a novella The Boy with Six Fingers (2025). In addition to this chapbook Boychik Poems, FLP will be published a collection of short stories Unknown & Other Stories in early 2026.