Fishing Pier and Hunting Lodge

An old man in hip boots stands in shallow water, just before it merges into the Chesapeake Bay, reeling in his fishing line and then casting again, re-baiting as the need arises with chunks of peeler crab he keeps in a pocket. He’s catching rockfish, the Maryland term for striped bass. He looks old, but he will get much older and toward the end of his life will build his own sailboat and sail alone on the bay. He looks at home standing in the water but does not know how to swim. Like other watermen, his skills involve staying afloat, keeping his vessel from capsizing, tonging for oysters and pulling up crab traps. He served for fifty years as commander of the Maryland Oyster Fleet, which means that above all else he’s a politician. He’s wearing a floppy hat because it’s sunny, but wind has started blowing, so he’s tied the hat under his bristly chin.

His daughter, the opera singer, has inherited his beautiful curls. Her press releases claim he’s a singer too, but his performances usually take place at night, on a boat or in the yacht club, when he’s drinking and belts out “Old Man River.” She’s given up touring for the time being and is wading in the bay, tentative in her black swimsuit that shows off her buxom figure. She’s learning how to swim. My mother, wearing a bathing cap and a frilly pink swimsuit, is teaching her, encouraging her to relax while she cradles her in her arms.

My father, a skinny veteran who wants to be a singer, is fishing on a rickety, zig-zag pier, but unlike Captain Amos he’s not catching anything. He’s singing, but the wind is picking up strength and I can’t hear the words, although it sounds like a straining attempt at an aria.

I’m sitting by myself about halfway down the pier, wishing I could swim but prohibited because of the ointment and bandage on the back of my right knee where a spider bit me. At least that’s how the two Carolyns—the singer and my mother—have diagnosed the oozing pustule, which looks like a miniature volcano.

The scene has taken on a glow, like a picture in a tiny shrine, lit by a votive candle. My wife would call it a “flashbulb memory.” It reminds me of Proust, how tripping over the uneven paving stones in the Baptistery of San Marco recalls a similar stumble in Combray. Wind invokes Wingate, a spit of uneasy land across from Lower Hooper’s Island, which is uninhabited. I gaze at a group portrait: Captain Amos, my mother, my father, and the “glamorous soprano” who’s come between my parents.

The wind accelerates, and clouds that appeared like a mountain range over a long, flat island and the wide bay have nearly reached us, lightning hitting the water and thunder grumbling. We retreat to a hunting lodge by the pier, where a caretaker latches the shutters and locks the door. We’re all afraid, except for Captain Amos, as rain tattoos the tin roof and wind rattles the shutters and whines under the doors and down the chimney into the big fireplace where the caretaker lights tinder for a fire, even though it’s August.

The funny thing is, I don’t remember the storm passing, or trotting out to the Chevrolet as the last drops of rain peter out. The windy, sunny day on the edge of the water always ends with a summer squall that traps us in the hunting lodge, like characters in Sartre’s No Exit. It’s the last time we find ourselves together in one room, a temporary refuge from the permanent storm, so I hold on and won’t let the light blow out.

Disclosure #3

I have never returned to the location of the most intense memory of my childhood. The lodge is probably long gone. But I wrote a poem about the experience over a decade before I began working on this memoir, a pantoum with a title that I knew was inaccurate, “Storm on Fishing Bay.” Composing the previous chapter allowed me to flesh out details, but the song-like qualities inherent in the repeating, circular Malay poetic form do underscore the musical interests of the main characters. Now that the poem is being reprinted, I’m giving it a new title: “Storm Approaching”:

What’s hard to explain

darkens the prospect of happiness—

like wind picking up off shore

where four people retreat separately.

Darkened, the prospect of happiness

falls back to a hunting lodge

where four people retreat, separately

latching shutters, brewing coffee, gazing.

Fall’s back. In a hunting lodge,

who is stirring the dust—

latching shutters, brewing coffee, gazing

at pictures spilled from an album?

Who is not stirring the dust?

The mother fussing? The boy who ponders

pictures spilled from an album?

The father quiet? The beautiful stranger singing?

The mother fusses at her boy, who ponders

what’s hard to explain:

the father quiet, the beautiful stranger singing

like wind picking up off shore.

The excerpts are from the book Bobby and Carolyn: A Memoir of My Two Mothers by John Philip Drury (Finishing Line Press), and can be found at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/bobby-and-carolyn-a-memoir-of-my-two-mothers-by-john-philip-drury/

Bobby and Carolyn: A Memoir of My Two Mothers focuses on the author’s mother and the “glamorous soprano” who came between his parents when he was eight years old. They both fell in love with her, but Carolyn Long and his mother, whose nickname was Bobby, ended up together, sharing a life and what they secretly considered a marriage, having exchanged vows on a moonlit night in the summer of 1958. This memoir celebrates the do-it-yourself union between two women: a housewife who became a bank teller and a professional singer who became a voice teacher. It endured until one partner’s death in 1991—memorialized by the cemetery plot they share, with their names engraved on opposite sides of the tombstone, just like the names of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Their life together was turbulent, partly because of their volatile personalities (and it took volatility to make such a leap of faith into forbidden love in the Fifties), partly because of prejudice against same-sex relationships, so they had to call themselves “cousins” in order to rent an apartment or a house together. Although the author grew up with the two women and considered Carolyn more of a parent than his father, he didn’t discover the true nature of their tumultuous relationship until both women had died and left clues for him to find in their diaries and notes.

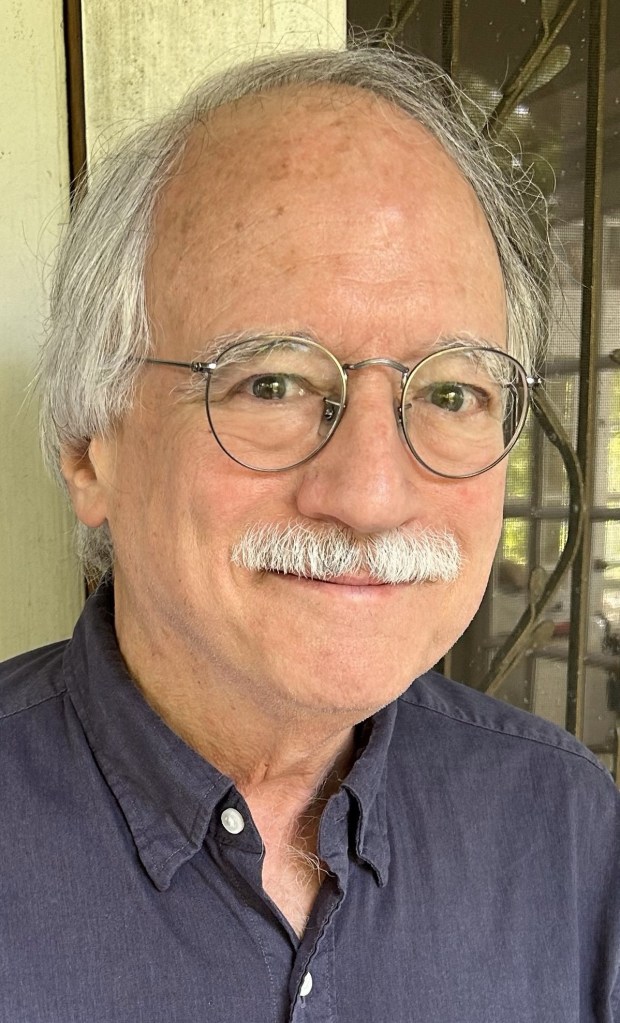

John Philip Drury is the author of six collections of poetry: The Stray Ghost (a chapbook-length sequence), The Disappearing Town, Burning the Aspern Papers, The Refugee Camp, Sea Level Rising, and The Teller’s Cage: Poems and Imaginary Movies. He has also written Creating Poetry and The Poetry Dictionary. His awards include an Ingram Merrill Foundation fellowship, two Ohio Arts Council grants, a Pushcart Prize, and the Bernard F. Conners Prize from The Paris Review. After teaching at the University of Cincinnati for 37 years, he is now an emeritus professor and lives with his wife, fellow poet LaWanda Walters, in a hundred-year-old house on the edge of a wooded ravine.